Top 13 Tips On How to Move to Iceland

- Why Move to Iceland?

- Living and Working in Iceland as a Foreigner

- How to Move to Iceland

- First Steps: Icelandic Residency and Work Permits

- Can EU Citizens Live in Iceland?

- Moving to Iceland from the US, UK, and Other Non-EU Countries

- The Kennitala - Icelandic ID Number

- A Roof Over Your Head

- Finding a Job in Iceland

- Money in Iceland

- Nature in Iceland

- Learning The Icelandic Language

- Healthcare in Iceland

- Education in Iceland

- Crime and Safety in Iceland

- Religion, Spirituality, and Atheism in Iceland

- Getting Around in Iceland

- Icelandic National Holidays

- Final Thoughts

Discover everything you need to know about moving to Iceland, from the immigration process to cultural habits, the benefits, and challenges in this guide. Since 2016, more than 10,000 people per year have decided to move to Iceland from elsewhere in the world. If you’re preparing to make a move, you’ll want to read this first.

- Learn all you need to know about Finding a Job in Iceland

- Find out How to Purchase Property in Iceland

- Explore the city on a Reykjavik City Tour

Why Move to Iceland?

It should come as no surprise that Iceland is often considered one of the planet's most desirable places to live. Nature here is majestic, dramatic, and sublime, a plethora of untouched wilderness and geological marvels. Life in Iceland is very much in tune with and intertwined with, nature and the elements.

The locals are friendly, welcoming, and open, speak fluent English, and enjoy their foreign guests’ company, however long they stay. On top of that, Reykjavik, as a capital city, is quintessential and charming, a bustling urban center that easily maintains its small-town feel, gentle pace of life, and devotion toward social progress and culture.

And the cherry on the cake? Since the 2008 financial crisis, Iceland’s economy has not only repaired itself but boomed in a way that no one expected. Unlike the rest of the world, Iceland went against expectations.

It let its three largest banks - and the bankers that came with them - fail and be jailed. The country also imposed strict capital controls, austerity measures, and financial reforms.

This dire economic situation allowed Iceland's financial sector to start anew. It laid the groundwork for a national economy that saved the country and thrust it into a bright and prosperous future.

And what does this future look like? Every year, more and more visitors arrive to experience life in Iceland for themselves. This small island nation has been making a big international impression.

In the time after the financial crisis, Iceland has become a European hub for culture, travel, and adventure. With such an enormous influx of visitors, it seems natural that many would be so taken with the country that they would consider moving to Iceland themselves.

And with such charming national qualities, it’s easy to see why Iceland might appear as the new promised land, an ice-wreathed paradise nestled beside the Arctic Circle.

Living and Working in Iceland as a Foreigner

Many who have moved to Iceland have had no regrets about the decision. Those who commit to this change will find life in Iceland open, accepting, and varied. It plays out at a gentler pace than other countries, which leaves more room for reflection, observance, and self-development.

Many find the island's small population - around 340,000 people - a surprising bonus. Iceland's fairly diminutive size acts as a foundation for community living, naturally enforcing fairness and acceptance with those around you. Quite different from the competitive pressure of life in a country with a population of millions or even billions.

That’s not to say living in Iceland doesn’t come with its difficulties. Some might find the fish-heavy diet a little unappealing, the brand choice often unsatisfactory, and the winter months long, cold and dark (psychologically, of course).

For the most part, however, the good heavily outweighs the bad, and day by day, Iceland will feel more like home.

For anyone interested in making the leap themselves, here is the most accessible and comprehensive guide to moving and living in Iceland available, including aspects of life that are less widely regarded by other expatriate guides.

It's time to pack your suitcase. A whole new world and a whole new life await you. How to live in Iceland is a matter of sorting out your legal standing and practical needs.

How to Move to Iceland

So, you've decided to live in Iceland. Now it's time to see how the immigration process begins. This will help answer the question, “can I move to Iceland?”

First Steps: Icelandic Residency and Work Permits

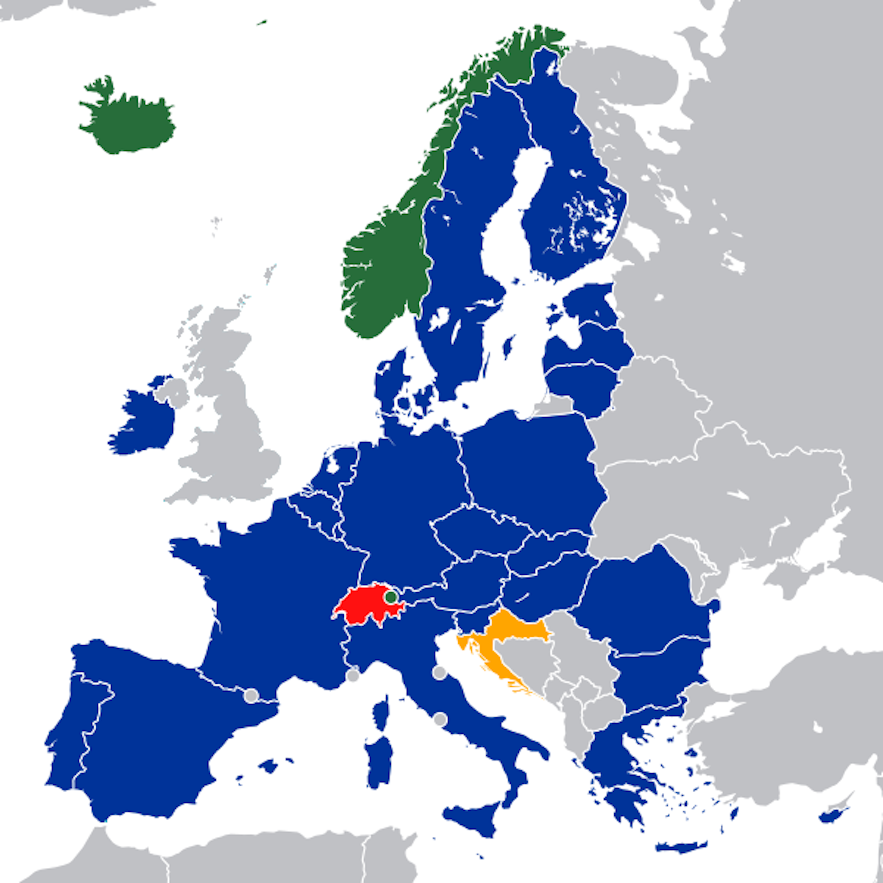

The above map shows countries that belong to the European Union (in blue) and those that belong to the European Economic Area (in green). Whether or not your home country belongs to one of these institutions is an important factor in moving to Iceland.

Can EU Citizens Live in Iceland?

Thankfully, EU, EEA, or EFTA (European Free Trade Association) citizens who intend to live and work in Iceland can enter the country without requiring special permits. They're allowed to work in the country legally for up to three months before needing to register a legal domicile. It's the perfect excuse to have an extended trip beforehand if only to scope it out!

This initial stay can be extended to six months for those seeking employment after they arrive.

However, after three working months, you must apply for a tax card. Those intending on long-term residency in Iceland must complete the form ‘Registration of an EEA or EFTA foreign national.’ This form serves as an application for an ID number and registration of your legal domicile in Iceland.

You can directly seek help from EURES (European Job Mobility Portal) or the Multicultural and Information Center for those who cannot provide the appropriate certificates. You register your legal domicile with the National Registry and must be able to demonstrate as part of your application that you can support yourself financially.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Adrian Pingstone. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Adrian Pingstone. No edits made.

Moving to Iceland from the US, UK, and Other Non-EU Countries

If you’re a non-EEA or EFTA citizen and wish to apply for long-term residency in Iceland, the process is notoriously more difficult but not impossible. There are three main lifelines:

- First, you could marry an Icelandic person, securing the right to live on your spouse's home turf. This option does require a pragmatic view on love, but it's not beyond the realm of possibility.

- Second, it's possible to use the student visa process and attend University in Iceland. This route is a popular method among younger people. It can provide you the benefit of study, purpose, and new friends upon your arrival in the country. However, hopping on to an Anthropology Masters program just because you want to move to Iceland doesn't sound like the wisest of decisions. Then again, tertiary education is excellent in Iceland, so why not continue to better yourself?

- The third method of obtaining residency is by securing a work permit. Naturally, this is easier said than done. In reality, the process appears to be a bureaucratic series of jumps and hurdles intertwined helplessly with Article 12 of the Act on Foreigners.

The Directorate of Immigration handles all applications for residence cards and residence permits in Iceland and any ID requests. Once the Directorate of Labor has issued you an approved work permit, you can begin work.

Note that you can only apply for work permits before traveling to Iceland. When both the work and residency permits have been approved, you are free to enter the country.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Antony-22. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Antony-22. No edits made.

Obtaining a work permit is difficult; laws prioritize Icelanders and EEA citizens above others. An applicant can try to nullify this by coming to the country with specialized skills. Below are the 3 types of work permits available to non-EEA/EFTA citizens:

- Qualified Professionals: Applicants are expected to have vocational training at a University level or a technical standard approved by Icelandic bodies. The work must be relevant to a permanent field lacking in Icelandic labor, and the applicant must prove that they can do the job better than an Icelander or EEA citizen.

- Athletes: Coaches and athletes belonging to a sports club within the National Olympic and Sports Association of Iceland may be allowed work permits.

- Temporary Shortage of Laborers: Permits may be issued to laborers in fields that are lacking in Icelandic workers or EEA workers. Therefore, these permits are only temporary and can only be renewed once. The Directorate of Labor provides a list of temporary work agencies.

The Kennitala - Icelandic ID Number

The kennitala is an Icelandic personal identification number, which is very much the same as a social security number and is required for almost everything you do in the country. If you would like to: rent property, receive a tax card, borrow books from the library, register with a doctor, open a bank account, buy a telephone, connect to the internet, and more, you'll need a kennitala!

The kennitala is ten digits long, made up of your date of birth (DDMMYY) and four randomized numbers at the end.

Many other countries across Europe use the kennitala system, but few utilize it in such an extensive manner, incorporating businesses and public institutions within it. For example, the University of Iceland uses the national identification system to distinguish their students rather than an internal system.

The kennitala is also essential to banking transactions in Iceland and serves as an alternative to the government census.

Kennitalas are administered by Registers Iceland, the official civil registry of the country. It's possible to live in Iceland for 3 months without the kennitala, but it will still be needed to access certain services.

An application can be made individually or applied for on the applicant's behalf by the employer. Note that obtaining a kennitala is not the same thing as registering a legal domicile, but usually, you can attain both at the same time at Registers Iceland.

Non-EEA or EFTA citizens cannot apply for an ID themselves.

For instance, if you need an ID for health insurance in Iceland, the insurance company. Secondapplies on your behalf. They send a form with a copy of your passport to the national registry.

Those same citizens who have obtained a national ID before entering Iceland are still not permitted any rights in the country until they have been issued a residence permit and have registered their address as a legal domicile.

A Roof Over Your Head

If you’re planning to live in Iceland, Reykjavik seems the logical choice. 70% of the country's population lives in the capital city, making it the island's urban and economic center.

Akureyri is the second biggest town, far to the north of the island, but opportunities for jobs and accommodation lessen significantly the smaller the town gets.

To put things in perspective, if you want to move to Reykjavik, you’re in for a significantly better shot at finding a job and an apartment than if you decide to move to, say, the sleepy fishing village of Dalvik (unless, of course, you happen to work in fisheries.)

There's a lot of competition for accommodation in Reykjavik. It's a small city that, in many ways, has been taken aback by the intense international interest Iceland has enjoyed over the last fifteen years.

Housing is one such area where this shock is visible. If time and finance allow, it's always wise for expats to find a place to live before moving. Nowhere is this more important than Reykjavik.

Icelanders tend to have a preference to own their house or flat. 80% of house stock is, in fact, privately owned, which makes the rental market pretty small for those coming from the outside.

Still, depending on your lifestyle preferences, there are numerous neighborhoods around Reykjavik from which to choose. It takes is time, patience, and a bit of determination, and you'll find a roof over your head in no time.

Below you'll find four examples of neighborhoods in the capital, plus the average rental cost for a two-bedroom flat.

- Midbaer - Downtown 101: This is the most highly sought-after neighborhood in the city. Here you’ll find the restaurants, bars, shops, and clubs that make up the Laugavegur strip. As can be expected, given the history of the area and the proliferation of amenities, this is where rental prices are highest. On average, monthly rent for a 900 square foot flat will put you back about 1,600 USD (210,000 ISK) a month.

- Vesturbaer: West Town is generally quieter than the downtown area but is still within easy walking distance to the city center. There are also excellent bus routes that stop every fifteen minutes, making downtown easily accessible. This area is less expensive than 101, meaning that rent prices, on average, for a 900 square foot flat will be around 1,450 USD (190,000 ISK) a month.

- Austurbaer/Hlidar: This area is to the east of downtown and is within easy walking distance to local amenities. However, it's noticeably quieter, with no bars or restaurants. As with Vesturbaer, this area is less expensive, but one should still expect costs of around 1,450 ISD (190,000 ISK) a month.

- Laugardalur: To the northeast of downtown, this district is a hub of activity for Reykjavik residents. It's home to incredible sports facilities, swimming pools, commercial businesses, and Reykjavik's lone campsite. Two/three bedroom flats range from around 1,250 - 1,450 USD (160,000 ISK to 190,000 ISK) a month.

Though rental costs appear to be quite high at first glance, there's a noticeable difference in the monthly price of utilities. Given that Iceland's primary energy source is geothermal, electricity, heating, and water costs are significantly less, making the overall sum of a month's rent more manageable.

It should also be reiterated here that national salaries reflect the cost of living, bringing the rental market somewhat into balance.

To make the competition fiercer (and the housing situation all the more complicated), many landlords can increase their profit margins by turning their flats into pop-up Airbnbs.

It's difficult to critique the ambition of doing so - the gold rush that coincides with the tourism boom is truly sizable, so it's no wonder that resourceful Icelanders are trying to catch a piece of this action for themselves.

There have been many known cases of landlords evicting their tenants to pursue the Airbnb market. This behavior has given a negative impression of the housing market and has made tenants noticeably cautious when choosing a place to live.

Getting a signed and sealed contract is crucial for long-term renting in Iceland. Given the Icelanders' tendency to be laid back about such things, this might be harder than you think.

Whatever the case, this sudden sprawl of Airbnbs has been one of the primary factors increasing housing competition in Reykjavik. Between January 2014 and January 2015, Airbnbs in the city increased by a whopping 137%.

In June 2015, 1800 apartments were being used as Airbnbs. There has been some recent legislation to peel back this trend, but so far, the situation continues to worsen.

Below are some property websites that could help movers in their search:

Finding a Job in Iceland

Iceland has a 99% employment rate, a statistic that is easy to be proud of. Thanks to the country's small population, prospering economy, and high level of education, job opportunities in Iceland have quickly moved away from the fishing and farming of yesteryear to encompass all the positions worthy of any modern democracy.

This is a country of financiers, tour guides, gourmet chefs, scientists, artists, teachers, construction workers, researchers, artisans, and academics.

It's always easier to find work while being a resident of the country you wish to work. Thus, finding employment beforehand will require a lot of patience, time, and awareness of any opportunities, laid the,

Finding work in any foreign country comes with difficulties, especially if the job seeker lacks basic foreign language skills. That's not to say it can't be done, however. Many who move here will realize that Iceland has opened its doors to the world and, without a doubt, will need both locals and foreigners alike to participate in the workforce actively.

Without relying too heavily on the old idiom, "It's not what you know, it's who you know,” networking in Iceland is an incredibly crucial job-seeking tool. Iceland is a small country, thus finding work outside of cafes, bars, and hotels can heavily rely on your people skills.

Reaching out directly to English-speaking companies is always a positive step, as it shows interest in the organization and actively gets you involved with talking to managers and employees. Even if that particular company isn't hiring, they'll know somewhere that is.

It's also crucial for individuals seeking work to continue to build upon their relevant skills. This effort shows commitment to your vocation and an attractive mindset, open to further development and self-education.

Whether practicing at home, undertaking a related study course, shadowing potential employers, receiving one-on-one coaching, or creating an action plan - all are greatly beneficial while on the road to finding employment. It's also easier to find work in Iceland for EU citizens than others.

Volunteering is also extremely useful, although no job-seeker likes to admit it to themselves. Volunteering is an excellent opportunity to meet new people, build upon existing skills, and give back to society. Employers will also be impressed that the applicant's time has been put to good use.

Below are some job sites that might come in handy for job seekers:

Money in Iceland

The 2008 financial crisis hit Iceland far harder than most other countries. The government immediately put in high austerity measures, forbade international transactions, and set about implementing economic reforms.

Protests were ongoing; thousands of people assembled outside parliament, demanding answers and justice. Many government ministers would eventually resign, given the pressure of the country's dreadful economic situation.

The main difference in the country's response to the crash was how Iceland dealt with its banks. Iceland's banks became fully privatized in the first half of this century and thus began an aggressive strategy toward economic growth, mainly by purchasing stock and property outside Iceland.

Unfortunately, their strategy was highly flawed, with many international economists declaring it 'suicidal.’ The bankers were overly reliant on borrowed funding, unbelievable interest rates, and an appetite for rapid expansion. As 2008 neared, international markets became wary of Iceland's runaway economy.

Whereas most other countries chose to bail out the bankers, Iceland did the honorable thing and took them to court, jailing many of the worst offenders. In many ways, this was the government's only choice; the banking system's overall worth was twenty times that of the national budget and ten times that of the country's GDP.

To make matters worse, 97% of the banking system collapsed within three days. Unlike elsewhere, bailing out the banks was not a viable option. Since the crash, Iceland's economy has steadily improved. By 2012, Iceland was regarded as a success story to come out of the financial collapse, having had two full years of economic growth.

This rebound was due to many reasons, the most important of which were the emergency measures put in place in 2008 to help alleviate the initial crash. As of 2020, Iceland continues to strengthen its economy and has recently pulled back on capital controls, making the transfer of money internationally far more accessible.

Icelandic Krona is the national currency of Iceland. Banknotes come in 500 ISK, 1000 ISK, 5000 ISK, and 10,000 ISK. Coins come in 1 (a highly useless piece of metal), 5, 10, 50, and 100. With a little bit of saving, it's easy to become a millionaire in Iceland. It doesn't have the same gravitas as elsewhere, unfortunately.

Like other Nordic countries, Icelanders will usually make all purchases by debit card.

One of the first things that visitors note about Iceland is how expensive the cost of living is. Unfortunately, this is simply the reality of living on a fairly isolated North Atlantic island. Importing items is expensive and, when they do finally arrive, there's a minimal amount of brand choice. This lack of options might shock the system for British or American visitors who are used to a wide selection of brands. It's sometimes referred to as the worst part about living in Iceland as an American.

The truth of the matter is the cost of living in Iceland is 55% higher than that of the United States. On average, renting an apartment in Iceland is 26% higher. To avoid ruminating any further, Iceland is the fourth most expensive country to live in worldwide. That statistic can be a difficult pill to swallow. The minimum financial support for a single person to survive in Reykjavik is estimated to be 1,600 USD (208,000 ISK) a month.

Nature in Iceland

Geologically, “the Land of Ice and Fire” is one of the youngest countries on the planet. It's rich with active and dormant volcanoes, stunning glaciers, and a wide array of cascading waterfalls and rivers. People are often struck by how fantastical the landscapes in Iceland appear. They look as though they were taken straight out of Tolkien's Middle Earth!

After all, where else can such open wilderness hide the geological marvels, dramatic mountain ranges, and eclectic hills and valleys that are so prolific in Iceland?

Iceland consists of several different regions: East Iceland, West Iceland, South Iceland, North Iceland, the Westfjords, the Reykjanes Peninsula, and the Highlands. All are fantastic for scenery, with each offering its own unique spectacles.

The black sand beaches to the south, for instance, greatly contrast with the white ridged ice caps of Vatnajokull National Park, even more so than the black desert of Holasandur. In terms of natural variety, there's enough here for a lifetime.

One of the surprising things about Iceland is its relatively temperate climate. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, Iceland enjoys more warm and sunny days than most people expect, especially from May to September.

The weather is renowned for its volatility. One might leave the house for a crisp and bright morning, only to return later that night in the face of blizzards and horizontal winds. Icelanders often say, "If you don't like the weather in Iceland, just wait five minutes."

In general, Icelanders tend not to recognize autumn or spring, simplifying their seasons to a long summer and a long winter. This lack of acknowledgment makes a lot of sense, given the intensity of the dark winter months in contrast to the waking life that comes with the ever-present midnight sun. The average temperature for January is 31 F (-0.5 C) while June sees average temperatures of 48 F (8.9 C).

The length and vigor of these seasons take a fair amount of getting used to and are bound to wreak havoc on your regular sleeping pattern. Throughout the summer, many Icelanders choose to black out their windows, for instance. Many people will take a daily dose of Vitamin D to keep their chemical balance normalized after a lack of sun in the winter months.

Icelanders are rightfully proud of their beautiful environment and maintain a solid connection to the natural world. There are three national parks in Iceland: Snaefellsjokull National Park, Vatnajokull National Park, and Thingvellir National Park. The first two parks center around two of Iceland's most prominent and majestic glaciers, while Thingvellir is the only park that is also a UNESCO world heritage site.

This UNESCO label is twofold; first, Thingvellir is where the historical parliament was formed and held in 930 AD, and second, it's where guests can see both the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates exposed from the ground. The resulting scenery is another example of the incredible geology so abundant across the island.

Iceland is also at the forefront of renewable energy, with almost all homes and buildings in the country heated geothermally. The Icelandic government is acutely aware of fishing management protocols and has created a sustainable system to keep fishing grounds prosperous.

Learning The Icelandic Language

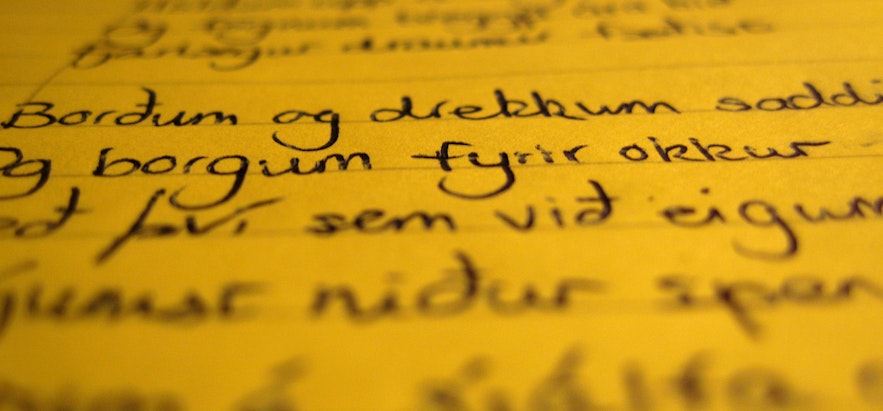

The Icelandic language can seem fairly inaccessible to the outsider. It’s spoken quickly, with stress placed on each word’s first syllable, a relatively unique speech pattern worldwide.

It's a Nordic branch of the Germanic language, different from its Scandinavian cousins, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It more closely resembles Old Norse, with a decidedly Celtic influence. The oldest preserved texts in Icelandic date back to 1100 AD.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Max Naylor. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Max Naylor. No edits made.

However, it's a widespread misconception that Icelandic is the same language spoken by early Viking settlers. It’s an assumption that is only partly true. As with every language, Icelandic has seen many changes throughout history.

The language has adopted many French, Latin, Danish, and Norwegian words. In part, this is due to the Christianization of Iceland and the need to understand and communicate new religious concepts.

There have also been many changes to the inflection of speaking, pronunciation, and written grammar. These modifications aside, it's true that Icelandic is more archaic than other Germanic languages. Written Icelandic has changed so little that ancient 11th Century sagas are readable to many Icelanders.

Newcomers to Iceland should understand that Icelandic has retained two letters from Old Norse, letters that are no longer in the English alphabet; the characters Th, þ (þorn, modern English "thorn") and Ð, ð (eð, anglicized as "eth" or "edh"). These characters will likely cause a world of trouble for the non-native speaker. There are, however, many classes that teach Icelandic, often for free.

Icelandic is still the language spoken at home and between countrymen, only put aside for English out of politeness and the perplexed expression non-speakers often sport. This usage has always been the case; the Danish had little effect on the lexicon throughout their rule, as did the British and Americans during their Second World War invasions.

The good news is that if you can speak English, you'll be understood. Icelanders speak perfectly fluent English and are taught it as a second language at school. That’s not to suggest it should be relied on.

The Icelanders are a proud people, proud of their history and proud of their language. Many in Iceland fear that Icelandic could become a dying language, which is all the more reason to learn. Icelanders themselves will be grateful for the effort.

- See also: Icelandic Literature for Beginners in Iceland

- See also: The Story of Icelandic Cinema

Healthcare in Iceland

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Vera de Kok. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Vera de Kok. No edits made.

Health insurance in Iceland is covered by the state, with individuals paying their contribution through taxes and service fees. A significant portion of the state budget is also focused on healthcare, a worthy feat given that Iceland has the highest life expectancy in Europe at 83 years.

There are six regional hospitals in Iceland and 16 health institutions (these may be clinics or teaching hospitals.) Privatized health insurance is a rare occurrence, and there are no private hospitals on the island.

112 is the number to dial for anyone seeking emergency medical services. If there's no emergency, but you still require medical assistance within the city limits, you should call 544-4114 during regular opening hours.

Outside of those operating hours, you should dial 1700, where an English-speaking nurse will offer medical advice, direct towards night-clinics or send staff for a house call. After hours, you can request dental care by dialing 575-0505.

Given the vast stretches of wilderness so prevalent in Iceland, air ambulances are an essential part of the country’s overall health care and emergency response. Aircraft and helicopters are split between hospitals in Akureyri, Reykjavik, and the Coast Guard, who will supply helicopters should no others be available.

EEA and EFTA citizens will find they're covered by Icelandic health insurance if they're European Health Insurance Card holders.

Education in Iceland

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by HerbertG. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by HerbertG. No edits made.

Icelanders have been blessed with an excellent education system for many years, holding to the island's robust learning and academic reputation. The government's view is that everyone should be entitled to the same education, regardless of sex, residential location, handicap, financial status, or religion.

Iceland splits education into four separate stages: playschool (ages 1-6), compulsory (ages 6-16), upper secondary (ages 16-20), and tertiary. Instruction focuses on promoting academic learning and is mandatory for everyone ages 6 to 16.

The vast majority of schools in Iceland are state-run and organized by the Ministry of Education. There are very few private schools on the island. Thankfully for newcomers, Icelanders learn English as a second language throughout their schooling.

Throughout compulsory schooling, pupils learn various subjects, including foreign languages (Danish, English, and other Nordic languages), ethics, mathematics, art, physical education, geography, history, social sciences, and affairs relating to equal rights.

The International School of Iceland is also in Greater Reykjavik. International schools are often the choice for expatriates looking to habituate their children to a new environment quickly. The International School of Iceland follows the British curriculum.

There are seven higher education institutions in Iceland, the principal one being the University of Iceland, founded in 1911. Below is a list of the countries' universities.

The vast majority of higher education institutions are state-run, which means that prospective students need only pay registration fees to begin their studies. Private institutions do require tuition fees. International students will find that many courses are taught in English (though an English exam may be required before attending.)

Crime and Safety in Iceland

Iceland has an excellent reputation for safety. Violent crime is an incredibly rare occurrence, and when it does happen, it’s usually the result of tourists smacking one another after one too many drinks.

From 2000 to 2009, violent crime events never rose more than 1.8 per 100,000 people. Consider the United States, which bounced between 5 to 5.8 per 100,000 people over the same period. Statistically, Iceland is the third least likely country to be murdered in, a comforting fact if ever there was one.

Surprisingly, when a violent crime occurs in Iceland, it rarely involves a gun. It’s surprising only given the high percentage of gun owners in Iceland: roughly 90,000 people. However, unlike elsewhere, acquiring a gun is a pretty difficult process and includes both a medical and written examination.

Pickpocketing has been reported around popular tourist attractions but is not a significant problem. However, with more and more visitors arriving every year, it's advised to keep a close eye on your valuables while walking around town or visiting some of Iceland's natural highlights. Be wary that pickpockets tend to work in groups.

Because Iceland is an island, drug use and the availability of said drugs are more limited than in the rest of Europe. Still, drugs are prevalent on the island, though hard substances such as heroin and cocaine are difficult, if not impossible, to come by.

It's illegal to own, use and carry drugs, and those who break that law can often face strict penalties; anyone caught in possession of less than 1 gram of any substance can face fines of around 230 USD (30,000 ISK). Drug-related crime in Iceland is a very rare occurrence, excluding drunk driving charges.

The terrorism threat rating in Iceland is low. While there was some concern over terrorist attacks across Europe in 2015 and 2016, there has proven to be no threat here.

- See also: Graffiti and Street Art in Reykjavik

Iceland is a member of the Schengen Agreement, which facilitates free movement between member countries. This openness has caused some alarm amongst locals, who fear that terrorists could easily cross international borders under the agreement.

Sex crime in Iceland is surprisingly higher than in other Nordic countries but still maintains a low-risk level compared to other major nations across Europe. Regardless, rape in Iceland met an all-time high in 2018. Rates have thankfully been declining since then.

Equal rights and the empowerment of women are essential cultural pillars in Iceland. For instance, prostitution, strip clubs, and businesses profiting from their employees’ nudity are illegal on feminist grounds rather than religious ones.

The Facebook group Beauty Tips is just one way Icelandic women have chosen to vocalize their frustration at the lack of progress in dealing with sexual and domestic violence. For example, ARC’s activism movement (Activism against Rape Culture) directly came out of the Beauty Tips Facebook group.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Dickelners. No edits made.

Photo from Wikimedia, Creative Commons, by Dickelners. No edits made.

The Icelandic Police - called Logreglan in Icelandic - comprises the Reykjavik Metropolitan Police and the National Commission of Police. The force is highly equipped with the latest technology and training to prevent, disrupt, and investigate crime throughout Iceland.

Many observers have claimed that Iceland has such low crime rates because its police force is expertly trained and well educated. Over 95% of the police in Iceland are unarmed.

Feel free to check out the Icelandic police on Instagram if you have any prior prejudice that might need altering in light of the Icelandic national character.

- See also: Gender Equality in Iceland

Religion, Spirituality, and Atheism in Iceland

Statistically, Iceland appears to be a pretty religious country. There are 41 registered religious groups, the biggest of which is the National Church of Iceland, an organization with 250,000 members (Icelanders are registered at birth, hence the significant figure). The National Church is organized under one diocese, administered by the Bishop of Iceland, Agnes M. Sigurdardottir, the first woman to hold the position.

Take a quick look online, and you'll see that today, approximately 80% of Icelanders are Lutheran while the majority of the rest are of other Christian denominations, namely Roman Catholic. You can find evidence of Iceland's historical commitment to Christianity in the number of churches dotted around the countryside.

The Christianization of Iceland occurred in the year 1000 AD, dramatically reshaping its culture and future. Under the Danish crown, Icelandic Christians were originally followers of Roman Catholicism before turning to Lutheranism (one of the main branches of Protestantism) at the end of the Icelandic Reformation in 1550.

Before this spiritual shift toward monotheism, Icelanders believed in multiple deities, the Norse Gods. Like their Scandinavian cousins, it was the mythological figures Odin, Loki, and Thor, who captured the religious fervor of Iceland's pre-modern population.

Since the first day of summer in 1972, Asatruarfelagid has also made a name for itself as a religious throwback to Icelandic/Nordic folklore. The organization was founded and led by the poet-farmer Sveinbjorn Beinteinsson, a man instrumental in gaining government recognition for the religion.

Asatruarfelagid has no dogma and no creed and instead relies on a pantheistic worldview based on an individual's connection to nature. As of 2016, the religion has approximately 3,200 members, a third of which are women.

Islam and Judaism have relatively small membership numbers. Iceland saw an increase in its Muslim population in the 1970s. It has around 900 people registered with either the Muslim Association of Iceland or the Islamic Cultural Center of Iceland. In 2002, the Reykjavik Mosque was opened.

There are approximately 90 members of the Jewish community, but their numbers are so small that Judaism is not officially recognized as a religious body by the Icelandic government. Today, there's no prayer house in Iceland catering to the Jewish people. The former first lady of Iceland, Dorrit Moussaieff, was a practicing Jew and did much to positively introduce the faith to the Icelandic people.

Another belief system that has gained prominence in Iceland is Zuism, a neopagan religion officially registered in 2013 but had existed for many years prior. In that same year, the belief system was mobilized by many new converts, mainly in protest of the "Parish Tax," a religious taxation imposed upon those with a spiritual inclination.

As one of the group's key pledges, any money earned from the parish tax was to be returned to the individual, thus making a mockery of the government's "God Tax" policy.

In reality, however, Iceland is a staunchly secular nation. According to polls compiled in 2014, less than half of Icelanders considered themselves religious, while 40% of the Icelandic youth declared themselves atheists.

At last check, less than 10% of Icelanders attend church once a month, while half of the population chooses to miss it altogether. In what's perhaps the most progressive statistic, a local January 2016 survey found that 0.0% of young Icelanders believed the world to be created by an ethereal craftsman.

However, that's not to undermine the Icelandic people's intrinsic connection to spirituality and the metaphysical. Many people believe in a personalized concept of God or in naturally determining forces.

Yoga, meditation, and Buddhist practices are common among the population, whether in nature, the water, or a pop-up event in downtown Reykjavik. Due mainly to the Icelanders' deep reverence for the natural world, spiritual practices originating from the far east have become a defining part of the national character.

For those who wish to do away with the supernatural entirely, the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association is the primary organization representing and supporting humanists in Iceland. The organization is registered with the Icelandic government as a life-stance group and can accept state funding, much like religious organizations do. As of 2017, the group has approximately 1,800 members.

- See also: Elves, Vikings and Norse Gods in Iceland

- See also: Witchcraft and Sorcery in Iceland

- See also: Yoga in Iceland

Getting Around in Iceland

Iceland is a big country. The open and wild terrain, be it mountainous, dried lava, or rocky shingle, demands visitors take their journey seriously. You can avoid ground travel altogether all year with one of the country's many domestic flights, but aside from that, a car will be a necessary purchase.

For those living in Reykjavik, a car is not absolutely essential. However, if you're going to be living outside the city or have a strong desire to explore the country, a vehicle will be necessary at some point. It's essential when purchasing a car to get a four-by-four drive, as many of the roads around Iceland are gravel or otherwise treacherous. Using a four-by-four is also unspeakably helpful during the winter when roads are often icy.

Iceland has a pretty perfect transport system. The buses are clean, well-maintained, and stick to a consistent schedule. You'll be waiting at the bus stop for a maximum of fifteen minutes at peak times in the capital. Navigating Reykjavik by bus is a straightforward affair and is often a good method for exploring the city’s less frequented corners.

There are no trains in Iceland, though there has been much talk in recent years about constructing a rail line between Keflavik Airport and Reykjavik. However, as of this moment, plans for the building are still very much in the air.

- See also: The Ultimate Guide to Driving in Iceland

Icelandic National Holidays

Iceland has numerous public holidays throughout the year to mark national celebrations. You can read them below:

1st January = New Year's Day

March/April = Maundy Thursday

March/April = Good Friday

March/April = Easter Sunday

March/April = Easter Monday

First Thursday after 18th April = First Day of Summer

1st May = Labor Day

May/June = Ascension Day

May/June = White Sunday

May/June = White Monday

17th June = Independence Day

First Monday in August = Commerce Day

24th December = Christmas Eve

25th December = Christmas Day

26th December = Boxing Day

31st December = New Year's Eve

- See also: Beer Day in Iceland

- See also: Best Annual Events in Iceland

- See also: Christmas and New Year's Eve in Iceland

Final Thoughts

Relocating to a new country takes an enormous amount of consideration and preparation. Even after organizing the visas, a place to live, and a company to work for, you must still overcome the mental hurdle of avoiding self-doubt and facing the darker realities of living life outside your current nation.

Seeing extended family will, undoubtedly, prove to be more difficult, as will visiting old friends, undertaking routine activities and habits. People who immigrate to Iceland can initially feel isolated or lonely on a cold and never-ending winter night. Perhaps the food is not to your taste, or the humor is inaccessible. These thoughts and feelings are all too honest for the global relocator.

Alternatively, you could grab life by the bullhorns and embrace the old saying, "life is not a dress rehearsal.” Ultimately the question of “should I move to Iceland,” is one only you can answer. However, nothing can quite shake up the mundanity of everyday living, like moving to a new country, and life in Iceland is nothing short of thrilling.

Other interesting articles

New Year's Eve in Iceland

What is New Year's Eve in Iceland like? What is New Year's Eve in Reykjavik like? What makes New Year's in Iceland special? Where are the best parties in Reykjavik on New Year's Eve? Learn all this an...Read more

5 Reasons Not to Behave Like Justin Bieber in Iceland

Justin Bieber came to Iceland to make the music video I'll Show You in 2015. You can see the result here above. Although Bieber fell in love with the country and decided to come back the following y...Read moreBeer Day in Iceland

1st of March is the Icelandic Beer Day. Beer was banned in Iceland between 1915 and until 1989! But why? Learn all about Iceland's history with beer. Photo above by Eeshan Garg. No edits made....Read more

Download Iceland’s biggest travel marketplace to your phone to manage your entire trip in one place

Scan this QR code with your phone camera and press the link that appears to add Iceland’s biggest travel marketplace into your pocket. Enter your phone number or email address to receive an SMS or email with the download link.